The decision of the

Bundesgerichtshof (BGH), the Highest Civil Court in Germany, in the Pechstein case was eagerly awaited. At

the hearing in March, the Court decided it would pronounce itself on 7 June,

and so it did. Let’s cut things short: it is a striking victory for the Court

of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) and a bitter (provisory?) ending for Claudia

Pechstein. The BGH’s press

release is abundantly clear that the German judges endorsed the CAS

uncritically on the two main legal questions: validity of forced CAS

arbitration and the independence of the CAS. The CAS and ISU are surely right

to rejoice and celebrate the ruling in their respective press releases that

quickly ensued (here

and here).

At first glance, this ruling will be comforting the CAS’ jurisdiction for years

to come. Claudia Pechstein’s dire financial fate - she faces up to 300 000€ in

legal fees – will serve as a powerful repellent for any athlete willing to

challenge the CAS.

Personally, I have, to put it mildly,

mixed feelings regarding this decision. On the one hand, I am relieved that the

BGH did not endorse the reasoning used by the Landgericht München in its ruling, challenging the necessity of forced CAS arbitration.

But, on the other hand, I am rather disappointed that the BGH failed to endorse

the balanced reasoning used by the Oberlandesgericht München in its decision (I translated the relevant

parts of the ruling here). I believed

this framing of the case would have offered a perfect vantage point to force a

democratic reform of the CAS without threatening its existence. For those

concerned with a potential flood of appeals, this could easily have been avoided

by barring Claudia Pechstein to prevail on the merits of the case (or through

preclusion for example). There was room for mild audacity and transnational

constitutionalism (as I argued elsewhere),

but the BGH opted for conservatism and conformism. I deeply regret it.

Though it is always perilous to

comment on a case based only on a preliminary press release, I will offer here some

(critical and preliminary) thoughts on the main aspects of the BGH’s legal

reasoning.

I.

This is not forced arbitration (or

is it?)

Paradoxically (or not), I chose to

start with the end of the BGH’s press release discussing the validity of the

arbitration agreement. The BGH is also very much drawn to paradoxes in this final

paragraph of its press release. In a first sentence it states rather bluntly

that Pechstein has freely signed the arbitration agreement in favour of the CAS.[1]

Yet, conscious of the absurdity of such a claim (unless one means only that

Pechstein was free to decide to become a professional speed-skater), it

immediately qualifies its assertion by claiming that in any case the fact that

she was forced to sign the agreement does not imply that it is invalid.[2]

This is justified on the basis of a balancing exercise (which is not detailed

in the press release and will be important to scrutinize in the final judgment)

between the athlete’s fundamental right to a judge and her freedom to provide

services and the constitutionally protected autonomy of associations (e.g. ISU).[3]

This is particularly so, because Claudia Pechstein could appeal a CAS award to

the Swiss Federal Tribunal (SFT).[4]

Thus, she had access to a national judge and did not necessitate recourse to

the German courts.[5]

Hidden in this relatively small

paragraph, compared to the overall press release, are many controversial

statements and assumptions. First, the claim that Claudia Pechstein (and any

other international athlete for that matter) freely submits to CAS arbitration

is surreal. So unconvincing, that the BGH itself debunks it in the following

phrase. What is it then? Free consent or forced consent? You need to choose! In

fact, CAS arbitration is always (in appeal cases) forced arbitration. This

should be openly acknowledged by the BGH and the SFT. Instead, they are forced

into logical convolutions that can only be perceived, in the SFT’s own words,

as “illogical”.[6]

Second, the balancing exercise conducted by the BGH should be scrutinized.

Unfortunately, there is very little information on this balancing in the press

release. Yet, one should not accept a restriction on the freedom of an athlete

to provide services and on its fundamental right to access national courts,

unless a forced CAS arbitration is shown as absolutely necessary to secure the

autonomy of the Sports Governing Bodies (SGBs). Moreover, such a weighty

restriction on the fundamental rights of an athlete should imply a strict

assessment of the quality of the judicial process at the CAS. In light of the

BGH’s assessment of the independence of the CAS (see more on this in part II.),

one can doubt that it has taken this balancing exercise seriously. Finally, the

claim that access to the SFT could compensate for the loss of Claudia

Pechstein’s access to German Courts is ludicrous, or in good German realitätsfremd. Any CAS practitioner

knows that the SFT favours (to its credit openly) a “benevolent”[7]

approach to the CAS, and that it is extremely reluctant to overturn awards

on the basis of procedural or substantial ordre

public.[8] Winning

an appeal against a CAS award in front of the SFT is a bit like Leicester City

winning the Premier League, an oddity.

Based on the BGH’s press release,

the ruling seems at best vague and unpersuasive and at worse negligent in its

assessment of the factual and legal situation. One can well argue that on

balance of interests, forced CAS arbitration might be necessary to preserve the

existence of international SGBs and their competitions, but this would imply a

way stricter assessment of the institutional independence of the CAS, which is

entirely lacking in the press release.

II.

The (in)dependence of the CAS

The core of the press release

concerns the independence of the CAS. The BGH considers that the CAS is a true

arbitral tribunal in the sense of German civil procedural law and that it is

not structurally imbalanced in favour of the SGBs.[9]

Therefore, forcing athletes to arbitrate disputes at the CAS does not constitute

an abuse of dominant position.

I contend that the BGH’s assessment

of the independence of the CAS is, based on this press release, imprecise and in

some regards even erroneous. It relies on four main arguments:

- SGBs and athletes share the same

interest in the fight against doping

- SGBs and athletes share the same

interest in having a uniform and swift sporting justice

- The CAS Code allows for sufficient

safeguards in case an arbitrator is not sufficient independent/impartial

- The athlete can appeal to the SFT to

challenge the lack of independence of an arbitrator

In the following sections of this

blog, I will aim at critically unpacking and deconstructing these four

arguments one by one.

A.

The shared interest of athletes and SGBs in the fight against doping

In a first paragraph, the BGH sets

out to rebut the OLG’s argument that the CAS is structurally imbalanced in

favour of the SGBs, i.e. due to the selection process of CAS arbitrators

included in the CAS list. In the past, and still nowadays, it is the ICAS, a

body constituted of 20 members nominated overwhelmingly by the SGBs, which

decides who gets to be on the CAS list. Currently, based on their official CVs available on the CAS’

website, 13 out of 20 ICAS members have direct links with SGBs. Hence, the

OLG’s reasonable assumption that the selection process of arbitrators could

lead to the perception that the CAS was in a way captured by the SGBs and prone

to favour their interests.

The BGH’s trick to rebut this

finding of the OLG is to merge the interests of the athletes and of the SGBs

into a shared objective of fighting against doping.[10]

This is, bluntly speaking, ludicrous. It would be like arguing that the

independence of the criminal justice is redundant, because both the State and

the accused citizen share an interest in public safety and security. This is

legal nonsense and is not up to the standards of the BGH. It is easy to discern

that beyond an undoubtedly shared concern for the fight against doping, the

athlete and the SGB involved in a particular dispute over a failed anti-doping

test have radically opposite interests. Consequently, the independence of the

CAS is crucial to ensure that the SGBs do not abuse their legitimate regulatory

and executive powers in an anti-doping dispute.

B.

The shared interest in a uniform and swift sporting justice

The BGH, thereafter, argues that the

CAS would be necessary to ensure the uniformity and swiftness of sporting

justice and that this would be also in the interest of the athletes.[11]

I actually share the view of the BGH on this need for a uniform sporting

justice embodied by the CAS. Still, the German judges fail to comprehend that

this argument can be used only to justify the post-consensual foundations of

the CAS, but is toothless to promote laxer standards of independence for the CAS.

The need for uniformity and swiftness might call for a single institution

having mandatory jurisdiction, but not for this same institution to be captured

by the SGBs or to fail to ensure due process guarantees. Here, ironically, the

BGH is laying the ground for a strict review: the recognized necessity of

forced arbitration calls for an impeccable CAS on the due process side.

C.

The CAS Code safeguards the independence/impartiality of CAS arbitrators

In the following sections of its

reasoning, the BGH argues that any remaining imbalance of the CAS in favour of

the SGBs could be remedied via the procedural safety mechanisms included in the

CAS

code.[12]

In the full judgment it probably refers to article S.18 CAS Code providing that

arbitrators have to sign “an official declaration undertaking to exercise their

functions personally with total objectivity, independence and impartiality, and

in conformity with the provisions of this Code” and to article R.33 CAS Code

stating that “[e]very arbitrator shall be and remain impartial and independent

of the parties and shall immediately disclose any circumstances which may

affect her/his independence with respect to any of the parties.” Based on

article R.34 CAS Code, any challenge of an arbitrator on the basis of the

latter provision must be submitted to the ICAS Board composed of six members, five of which are or

have been in the past involved in executive positions in SGBs. In these

conditions, it should be obvious that challenging the independence of an

arbitrator vis-à-vis the SGBs is

extremely unattractive for an athlete, even more so when considering that in

case of failure there is a risk of alienating the arbitrator in question. This

is why the CAS’s independence issue is systemic and cannot be solved without

re-designing the selection process and composition of the ICAS.

Furthermore, the BGH also argues

that both parties can chose an arbitrator and that both arbitrators will then

designate the President of the panel.[13]

This is plainly wrong. In appeal cases, concerning almost all the anti-doping

cases and which was the procedure followed in the Pechstein case, it is the President of the appeal division that

designates the President of the panel.[14]

The president of the division is also the one in charge of ensuring “that the

arbitrators comply with the requirements of Article R33”. [15]

This person is directly nominated by

ICAS and it suffices to remind that the previous holder of this position was

(until 2013) Thomas Bach (now IOC President, then IOC Executive Board member),

to demonstrate how doubtful its independence from the SGBs was and still is. It

is difficult to understand how such a basic mistake has found its way into a

BGH press release. Even the official CAS Code Commentary by the CAS Secretary

General openly justifies this exclusive prerogative of the President of the appeal

division by stating that she “can better evaluate if it is preferable to

appoint an experienced arbitrator in order to act as chairman of the Panel or a

less experienced CAS arbitrator, who is not widely known to the parties but who

would have the necessary background to rule on a particular case”.[16]

The dilettante manner in which the BGH has conducted its assessment of the CAS’

independence contrasts strongly with the OLG’s thorough discussion of the

problematic role of the ICAS and of the president of the appeal division.[17]

D.

The SFT’s control of the independence/impartiality of CAS arbitrators

Finally, and this is a point already

touched upon in the first part of this blog, the BGH insists that the losing

party has the possibility to appeal to the SFT, which can annul the award.[18]

The problem is, again, that the SFT is a mere paper tiger. Yes, it intervened

(mildly) in the famous Gundel case in

1993, because back then the IOC was directly and openly controlling the CAS,

but since then it has adopted a very narrow interpretation of the scope for

challenges of the independence of CAS arbitrators.[19]

Generally, the SFT considers the CAS as a necessary evil that should be (very) benevolently

checked. This is hardly a credible avenue to ensure that its decisions abide by

the democratic standards called for on the basis of its mandatory global

jurisdictions.[20]

Conclusion: A missed opportunity

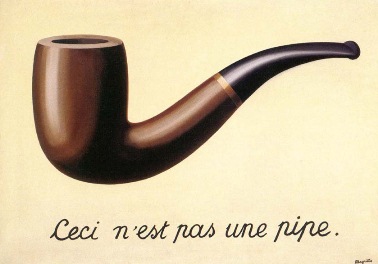

In work of arts, I am, and remain, a

fond admirer of Magritte’s surrealist take on life. Yet, I doubt that a Court

should engage in a similar exercise when drafting its judgments. Its role is to

get its facts right (or close to right) and find the fitting interpretation of

the law in a particular context. In the present case, I believe the BGH failed

on both fronts. In its press release it misrepresented basic facts (that can be

checked in two clicks via google) on the functioning and institutional

structure of the CAS, often concerning facts that were already available in the

OLG’s judgment. This is extremely worrying for such a reputable Court.

Additionally, it failed

to properly understand its constitutional role vis-à-vis the CAS and the need to ensure that basic due process

rights of athletes are respected at the CAS. This needed not entail the death

of the CAS, nor the end of its mandatory jurisdiction, nor even that Pechstein should be allowed to have her liability

claim heard (a flood of appeals could have been easily avoided). Instead, a

reform of the CAS could have been simply achieved by a subtle Solange formula stating roughly that

forced CAS arbitration is fine ‘as long as’ the independence of the CAS is

safeguarded and the due process rights of athletes warranted. Hopefully, the

case will move to the Bundesverfassungsgericht (and it is still pending before the

European Court of Human Rights), which knows a thing or two about Solange formulas…

[1] “Die Klägerin hat die

Schiedsvereinbarung freiwillig unterzeichnet.”

[2] “Dass sie dabei fremdbestimmt

gehandelt hat, da sie andernfalls nicht hätte antreten können, führt nicht zur

Unwirksamkeit der Vereinbarung.”

[5] “Ein Anspruch gerade auf Zugang

zu den deutschen Gerichten besteht danach nicht.”

[9] “Der CAS ist ein

"echtes" Schiedsgericht im Sinne der §§ 1025 ff. ZPO.”

[11]“Die mit einer

einheitlichen internationalen Sportsgerichtsbarkeit verbundenen Vorteile, wie

etwa einheitliche Maßstäbe und die Schnelligkeit der Entscheidung, gelten nicht

nur für die Verbände, sondern auch für die Sportler.”

[18] Die unterliegende Partei

hat die Möglichkeit, bei dem zuständigen schweizerischen Bundesgericht um

staatlichen Rechtsschutz nachzusuchen. Das schweizerische Bundesgericht kann

den Schiedsspruch des CAS in bestimmtem Umfang überprüfen und gegebenenfalls

aufheben.